An ex gratia policy probably puts some public pressure on the political executive to take note of grievances, and also incentivises people to get themselves tested or admitted, if at all, only to get a Covid-19 positive report.

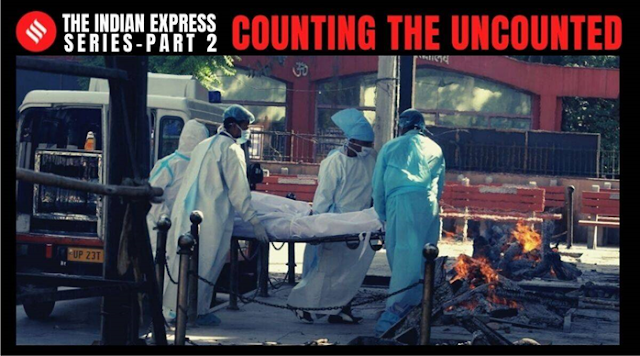

MANY states have noted a surge in their registered deaths in the months of April and May, the two months worst hit by the brutal second Covid wave, but most of them are yet to draw up any concerted plan to investigate how much of the surge is because of Covid.

The Indian Express, in the first part of this series, reported Wednesday that the cumulative all-cause deaths during April and May 2021 of eight states — Kerala, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi, Punjab, Haryana, Jharkhand and Bihar — was 1.87 times the April-May 2019 all-cause deaths (2019 chosen for comparison, it being a non-pandemic year).

Only two states, Bihar and Karnataka, seem to have acknowledged this unusual increase. Factoring in their official Covid death toll for these two months in 2021 — 3,587 in Bihar and 16,504 in Karnataka — their multiplier works out to 2.03 times in Bihar and 1.37 times in Karnataka.

Both states have decided to widen the definition of Covid-19 deaths, especially for purposes of providing ex gratia to affected families.

In Bihar, a doctor can attribute the cause of death to Covid-19 on the basis of lung infection in a High Resolution CT report and the line of treatment followed. Similarly, in Karnataka, if a patient did not have a Covid-19 positive report and was treated symptomatically with “clinical, radiological evidence and other laboratory values suggestive of Covid-19”, families can claim compensation provided the death is so certified by a qualified doctor.

These are modest yet significant attempts, given the tedious and complex process of counting the dead in India, and inefficiencies in capturing data on the cause of death.

Senior state and Central government officials, who do not wish to be named, said the present system is rigid and does not allow attributing any death to the viral infection in the absence of a Covid-19 positive report, hospital admission, or certification by an attending doctor.

There could be many such people in rural India, and even among the urban poor. “It is a problem. Death from Covid will be recorded only when the person was in hospital, was being treated for Covid, and passed away. What happens when you are not even being treated despite having Covid…in all likelihood, it would not be put down to Covid at all,” said Pronab Sen, Chairman, Standing Committee on Economic Statistics, set up by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, and former Chief Statistician of India.

An ex gratia policy probably puts some public pressure on the political executive to take note of grievances, and also incentivises people to get themselves tested or admitted, if at all, only to get a Covid-19 positive report.

In terms of compensation, Bihar is an exception with a substantive universal ex gratia policy — it pays Rs 4 lakh from the CM Relief Fund to every family which has lost a member to Covid-19. So far, it has received over 8,000 claims for compensation; the expansion of coverage has brought in another 3,000 applications of suspected Covid-19. The cumulative official Covid death count in Bihar as of Wednesday is 9644.

Karnataka pays Rs 1 lakh compensation to BPL families if they have lost a member to Covid-19.

Several states have prioritised only specific groups — orphans, widows, BPL families, frontline/ healthcare workers, journalists, government employees — for financial support.

On its part, the Centre has been reluctant to provide ex gratia, and argued in the Supreme Court that it had consciously decided to use funds under the National and State Disaster Relief Funds for providing food to migrant labour, for vaccination, and creating health infrastructure such as hospitals and ICU facilities.

The court, however, directed it on June 30 to frame guidelines for ex gratia payment to families of those who died — officially 4,25,757 as on date — of Covid-19 within six weeks.

Were the Centre to do so, all those who died probably of Covid-19, but couldn’t produce a Covid-19 positive report, will still not benefit from the ex gratia policy. “Anything in excess of the estimated death numbers (population multiplied by the death rate) bears an investigation… But were the excess deaths due to Covid as a disease or did they also happen due to lack of treatment? Remember, many people couldn’t access medical facilities during the pandemic. Here, we run into a conceptual problem,” Sen noted.

In response to The Indian Express report, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare said on Wednesday admitted “some cases could go undetected as per the principles of infectious disease and its management”, but ruled out missing out on deaths as “completely unlikely”.

In a statement, it said, “This could be seen in the case fatality rate, which as on 31st December 2020 stood at 1.45% and even after an unexpected surge observed in the second wave in April-May 2021, the case fatality rate today stands at 1.34%.”

The Ministry also said that during the peak of the second wave, correct reporting and recording of Covid deaths could have been delayed, but was reconciled by the States/Union Territories. This was because the health system was focused on effective clinical management of cases requiring medical help. “The reconciling of deaths is still being carried out allaying all speculations of underreporting and undercounting of deaths due to Covid,” it said.

Statistically, it may be possible to arrive at an estimation of the actual Covid-19 death count. “If you do a proper random survey of the deaths that have taken place during the period, X per cent was probably due to Covid. This can then be applied to the whole area. This solves your estimation problem, but doesn’t solve the identification problem,” Sen said.

Then, can a nation-wide door to door survey help identify those who died of Covid-19 as opposed to the official estimates?

Sen said this is the kind of stuff that is done in determining statistically the post-mortem cause of death. One state, Jharkhand, which conducted a door-to-door Intense Public Health Survey to arrive at the number of deaths in April-May decided to undertake another survey to arrive at the cause of death, said Arun Kumar Singh, Additional Chief Secretary, Health and Family Welfare, Jharkhand.

He, however, added that this, too, would not be address the gap between the official Covid-19 death count and those who might have died of Covid but could not establish so.

“Here, questions are asked about the conditions leading to death. What symptoms did the person show? It is based on recollection by family members, but done by an expert. But for this, you need a medical professional; anganwadi workers cannot do this. I don’t think we have the infrastructure to undertake such an exercise. Particularly at this juncture, it may not be a good idea to pull out doctors of their treatment responsibilities in the times of a pandemic that is still very much present, and put them on to this,” he said.

(With Iram Siddiqui in Bhopal, Navjeevan Gopal and Varinder Bhatia in Chandigarh, Shaju Philip in Thiruvananthapuram and Mallica Joshi and P Vaidyanathan Iyer in New Delhi)